- Home

- > Nature online

- > Earth

- > Natural disasters

- > Volcanoes

- > Studying volcanoes

Primary navigation

Studying volcanoes

Fieldwork at Popocatépetl volcano, Mexico

In 2013 Museum scientists Chiara Petrone and Dave Smith travelled to Mexico to study Popocatépetl, one of the world’s most dangerous and active stratovolcanoes.

During the trip they worked alongside Professor Hugo Delgado-Granados, a researcher from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Find out about the field trip by browsing the slideshow below.

Smoking mountain

At 5,450m, Popocatépetl is Mexico's second highest peak and its most active volcano. Popocatépetl is an Aztec name meaning smoking mountain.

Living in the volcano's shadow

The nine million residents of Mexico City are just 70km away. A large eruption could easily threaten many lives.

Image: amateur photo of smoke rising from Popocatépetl, taken from Mexico City.

The long ascent

After driving to the lower slopes of the volcano, the team begin their climb to find good places to collect rock samples.

Collecting rock samples

A large number of samples have to be taken to build up a picture of how the volcano has behaved in the past.

Some of these rocks are split open then crushed so they can be studied in detail. Others will become part of the permanent collection at the Natural History Museum.

Sampling different layers

Dr Chiara Petrone takes samples from different layers of the rock. These layers reveal past eruptions. Popocatépetl has had seven massive eruptions in the past 23,000 years.

Adding to the Museum collections

Back at the Museum Dr Dave Smith and Dr Chiara Petrone unpack and sort the rocks. They will study them to find out what kind of risks the volcano poses, and if another large eruption should be expected.

A number of the rocks collected are labelled and become part of the Museum’s collection.

Analysing samples

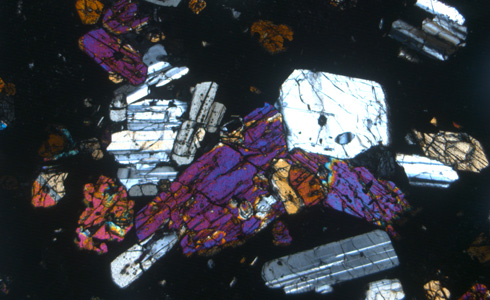

The remaining rock samples are used for scientific analysis. They are sliced or ground down to be scrutinised under the microscope.

Using microscopes and other more cutting-edge techniques, Museum scientists can observe the crystals inside the rock.

Tell-tale crystals

Crystals in volcanic rock samples reveal what was going on in the magma chamber when they formed, before they erupted out of the volcano.

This research not only tells scientists about this particular volcano, but the findings can be useful in understanding similar dangerous volcanic systems.

- Contact and enquiries

- Accessibility

- Site map

- Website terms of use

- © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

- Information about cookies

- Mobile