Bryozoans

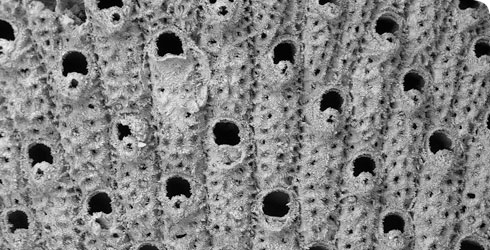

One group of animals that can reveal past temperatures are bryozoans. These small aquatic creatures have chalky skeletons that may fossilise after the animal dies.

Colonies of bryozoans are made up of individual members called zooids and their size is a clue to the temperature of the ocean when they formed.

Former Museum research student Tanya Knowles has studied variations in zooid size in fossil bryozoans from places around the north Atlantic, where they are very common and well preserved.

Zooid size and temperature

We know from studies of living bryozoans that the larger the zooid, the colder the temperature it was formed in.

By studying zooid sizes in fossil bryozoans from different places, Tanya was able to work out how temperatures varied through the year at different latitudes (distances north from the equator).

Tanya studied fossil bryozoans from the Pliocene Epoch of Earth’s history around 3 million years ago. She chose this period because the CO2 levels in the atmosphere at that time were probably similar to those that are likely to occur if CO2 levels continue to rise as a result of human activity.

Her results can be compared with existing climate models to find out which models best fit her data.

Isotope analysis

Like ice cores, bryozoan skeletons can also be used for isotope analysis.

There are 2 common types (isotopes) of oxygen molecules, known as 18O and 16O. 18O is more common in colder conditions.

Tanya calculated the proportions of 16O and 18O molecules in bryozoan samples to find out the temperature of the seas they lived in.

Uses of research on bryozoans

Tanya’s research could be used to help analyse the Earth’s temperature at times in its history, as well as the mid-Pliocene Epoch she has already studied.

Measuring variations in bryozoan zooid size is a particularly useful way of finding out about temperature because bryozoans are very common and they are found all over the world.

Toolbox

There are 27 km of specimen shelves in the Darwin Centre - the same distance as between the Museum and Junction 6 of the M1.