Norman MacLeod discusses missing links

Prof Norman MacLeod studies the origin and maintenance of form in fossil and modern organisms using mathematical models of shape variation. He also creates new mathematical tools for studying plant and animal form and develops computer vision - form analysis systems for automating the identification of species.

Missing links

What is a missing link?

Most species of organism that have lived on Earth have gone extinct, sometimes after producing a few descendant species.

But in a few cases, a seemingly inconspicuous species has given rise to one or more successful daughter species. These in turn gave rise to other successful daughter species, and so on. Eventually, a great and diverse branch of the tree of life is established.

A missing link is a fossil of the ancestral species of this major new lineage.

Why are they important?

Scientists seek to understand why some evolutionary lineages diversified and flourished while others did not. That is why there is intense scientific interest in ‘missing links’.

What did they look like? Where did they live? When did they live? And most importantly, what adaptations contributed to their own and their daughter species’ success?

None of these questions can be answered definitively without the evidence provided by fossils.

Features of missing links

Humans inherit the blended characteristics of a mother and a father, but species descend from other species, not combinations of species (with the exception of hybrids). Therefore, a true ancestor should pass on all of its morphological attributes to its daughter species even if some of them are present in an altered form.

For example, birds do not display the teeth of their dinosaur ancestors. But they still have the developmental systems needed to form teeth and do so on occasion (eg hens’ teeth).

This means that, in order to be recognised as a true ancestor, a fossil must have no unique morphological characteristics.

Problems with finding missing links

When inspected in detail, most of the classic missing link fossils, including the famous dinosaur-bird fossil Archaeopteryx, have some unique morphological features.

This suggests these ‘missing link’ species represent small branches of the tree of life, close to the common ancestor of descendant groups, but not fully representative of the actual ancestor.

Is Ida a missing link?

The status of Ida as a missing link is controversial.

Ida lacks some of the features common to modern lemurs but does not appear to possess any features unique to our own lineage of anthropoid primates. This makes Ida’s evolutionary status ambiguous at best.

It certainly does not suggest she should be given missing link status at present.

Scientists await a full description of the Ida fossil with detailed comparisons to the morphological features present in early primates. The controversy cannot be resolved until these comparisons are made and published.

Common descent

The tree of life

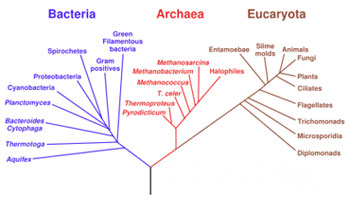

Ever since the late-1800s most biologists have accepted the idea that all living species are joined with the incomparably larger number that existed in the past. Their single genealogy is usually shown as a tree-like branching diagram – the tree of life.

A phylogenetic tree of life © NASA

The Scala Naturae

The belief that all species are linked goes much further back in time.

The ‘link’ in the term ‘missing link’ refers to the pre-Christian idea of the Great Chain of Being or Scala Naturae.

All matter, from simple, inanimate, physical materials to the most complex, animate, self-aware biological structures (such as man), were thought to exist in a smooth gradation of increasing complexity.

Apparent gaps in this sequence—the ancient missing links—were thought to be filled by plants and animals that existed somewhere on earth, but had yet to be discovered.

Common descent

As explorations proceeded some gaps persisted. By the early and middle 1800s a rival theory, common descent, was being promoted to account for these gaps. This theory also explains other evidence that challenged classical Chain of Being theory and its Christian variant that a great an benevolent Creator was responsible for the chain’s creation.

The tree of life shows the common descent of all organisms that have ever lived on Earth.

The evidence

Transitional forms

Nothing brings home the evidence for evolution quite like a true transitional form. This explains the importance of fossils like Archaeopteryx. It was recovered from a quarry near Solenhofen in Germany and it links birds to dinosaurs. It was an overnight sensation.

Since 1861 a large, number of transitional fossils have been identified. These document the transitions between primitive fish and sharks, fish and amphibians, amphibians and reptiles, various reptile groups, reptiles and mammals, and various mammalian groups. There have also been an even larger number of transitions among invertebrate lineages.

When Charles Darwin wrote On the Origin of Species, he argued that missing links must exist, but lamented the fact that so few had been recovered. Fossils like Archaeopteryx helped to fill this gap.

Creationist groups mistakenly believe that the failure to identify more transitional forms contradicts evolutionary theory. However, it is simply a consequence of an incomplete fossil record. The Ida fossil is thought by its authors to fill one of these gaps.

Morphological evidence

The morphological evidence supporting evolution does not lie in the bodies of transitional forms so much as in common features such as hair, milk teeth, feathers, four limbs, gill slits at particular stages of life cycle, styles of reproduction, etc.

The distribution of these features across species is arranged in a strictly structured, hierarchical manner, just as evolutionary theory predicts.

The morphological evidence for evolution via common descent is all around each of us every day.

Toolbox

In World War II the Museum was used as a secret base to develop new gadgets for allied spies, including an exploding rat!