Hammerhead shark helps investigate sense of smell

A shark can detect a drop of blood in water up to a kilometre away. But how?

Scientists know that sharks smell by detecting molecules in the water that flows through their nostrils as they swim.

To investigate how this water flows, scientists used the Museum’s micro-CT scanner to make the 3D model of a shark’s head that you can see in the video above. The CT scans were also used to make a real model that could be tested in a water-flow simulation tank.

Shark model is placed into the flow tank © Nic Delves-Broughton /University of Bath

Dr Jonathan Cox of the University of Bath who led the research explains. ‘The nasal cavity of the hammerhead is like a labyrinth of pipes. The smaller channels contain the olfactory receptors, and so we’re looking at how the water flows through these channels as the shark swims forwards.’

To investigate, the scientists needed to create a 3D model of the shark’s head and nostrils that they could use in a water-flow simulation tank.

Creating a 3D model shark

The first step was to get an accurate image of the internal workings of a shark’s head. To do this, the scientists put the Museum’s 50-year-old hammerhead shark specimen through the micro-CT (Computed Tomography) scanner.

The CT scanner takes thousands of very detailed images as it passes over the shark. These were combined to create the 3D image above. A very high-resolution version was used to ‘print’ the actual model that went into the flow tank. The model, including its internal cavities, is accurate to 200 micrometres (1 micrometre is 1/1000th of a millimetre).

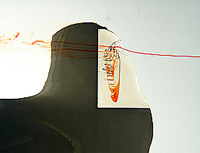

Dyed water flows through the shark model © Nic Delves-Broughton /University of Bath

Water flow simulation

In the simulation tank, the scientists could watch how water flowed though the model shark’s nasal cavities by putting a small amount of coloured dye in the water

They could also change the angle of the model to reflect how a shark turns its head from side to side as it swims. This is the first time shark sense of smell has been studied in this way.

Wider applications

Research into the hammerhead’s amazing sense of smell could help research in other fields where detecting chemicals is important, such as underwater exploration, environmental pollution or even counter terrorism.

Team work

The research project was led by Dr Jonathan Cox of the University of Bath and the team included scientists from the Universities of Bath and Cambridge as well as the Natural History Museum.

This research combined the expertise of scientists, CT scanners and fluid mechanics. As Dr Cox explains: ‘The nice thing about this project is its interdisciplinary-ness. Museum curators, CT specialists and engineers all had a hand in its success. Without them the project would have fallen flat on its face.'

Dr Richard Abel, Museum Micro Tomography Specialist who scanned the shark said: 'This is an excellent piece of research. The project utilised a very old Museum specimen to answer fundamental and wide-reaching questions by applying cutting edge technology and expertise.'

The research is published the scientific journal: Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A, volume155, pages 464-475, 2010.

Hammerhead sharks

The shark species used in this research was a smalleye hammerhead, Sphyrna tudes. There are 8 hammerhead shark species, the largest being the great hammerhead, which has been reported to grow to just over 6m.

Hammerhead sharks are fish. However, they do not lay eggs but instead give birth to live young, a process known as viviparity. They belong to the genera Sphyrna and Eusphyra ('sphyrna' is Greek for hammer) and their bizarre hammer-shaped head is thought to help them sense electrical signals, which they use to detect prey. Rays are a favourite food, but they also feed on fish, crabs, squid, lobsters and other sea creatures.

Toolbox

Art, nature and imaging

Discover how natural history art and imaging techniques have developed since the 17th century and explore selected artworks from the Museum’s world-class art collections.