Jaws: The natural history of sharks

Michael Bright

Threats to sharks and conservation

Sharks need friends. All over the world, sharks are big business, and over 150 million are slaughtered each year as the demand for shark products increases: sharks are prime targets for sports anglers; shark meat is low in saturated fats and high in polyunsaturated fats so shark steaks have been replacing red meat on sale in supermarkets; shark-liver oils are added to cosmetics and health-care products because they are the nearest inexpensive oils to natural skin oils; shark is turned into luxury leather for shoes, handbags and wallets; shark teeth are used as ornaments and in jewellery; shark cartilage can be a substitute for human skin to make artificial skin for burns victims; shark corneas have been used as successful substitutes for human corneas; a course of freeze-dried shark cartilage pills is claimed to arrest the growth of tumours; but by far the biggest and most lucrative market is dried fins for making into shark fin soup.

Shark fin soup

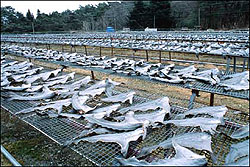

Row upon row of shark fins dry in the sun at Kesennuma, a centre for shark fins in Japan. Included here are the caudal (tail) fins of blue sharks. (Image: Mako Hirose / Seapics.com)

Shark fin soup is produced mainly in the Far East. It is a clear, glutinous broth that has been prepared from dried shark fins using traditional recipes for over 2000 years. Once a rare delicacy, consumed only by Chinese aristocracy, it is today a gourmet food on sale, for up to US$150 a bowl, in specialist restaurants worldwide. Such is the demand for fins and the remuneration so great, unscrupulous fishermen catch sharks, cut off their fins and throw their living bodies back into the sea, where they cannot move or swim and either starve to death or drown. This barbaric practice is known as 'finning' and thankfully it is now illegal in certain parts of the world, including in US waters.

Ironically, nature is about to get her own back. The traditional way in which shark fin soup is prepared means that the water content is reduced when the fins are dried and any impurities are concentrated. Nowadays, shark fins are laced with marine pollutants, such as mercury, and tests conducted at the University of Hong Kong discovered that the fins they analysed contained 5.84 parts per million (ppm) of mercury, compared to a maximum permitted level of 0.5 ppm. In Texas, similar tests with fresh sharks have revealed mercury levels up to 15 ppm, together with various other heavy metals, such as lead, even before the fins were dried.

Shark fin soup is said to be an aphrodisiac, and many people consume it specifically for this supposed property, yet the Hong Kong researchers also revealed that, because of the high mercury content, eating shark fin soup could render men sterile--the opposite of the intended effect.

Overfishing

With all this commercial interest, the temptation is for fishermen to catch every shark they can find, no matter what the biological or economic consequences. Shark fisheries, like the whaling industry before them, tend to follow a simple and predictable cycle of boom-and-bust. The problem is that sharks are slow to make more sharks, and if the breeding population is removed wholesale, the shark population and its fishery collapses.

The sandbar shark, which was caught commercially in the north-west Atlantic, illustrates this predicament. The species takes up to 30 years to mature; sexually mature females have offspring every two to three years and they have no more than 14 youngsters at a time, many of which fall prey to bull and tiger sharks before their first birthday. With a slow turnover like this, the population is slow to recover from heavy exploitation. In the sandbar's case, the problem is made worse because it passes from one local fishery to the next on its long-distance migrations in and out of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. The travelling population is diminished not once, but several times.

However, sharks that do not travel far are not excluded from suffering huge losses. For a shark population that remains in a small geographical area, commercial fishing could be nothing short of devastating and some populations fail to recover at all. A classic example was the rise and fall of two basking shark fisheries on the west coast of Ireland.

Basking sharks used to be a common sight from the coats of Ireland but a long history of overfishing has drastically reduced their numbers. The fishing was banned 40 years ago but because the sharks mature and reproduce slowly, their population has not recovered. (Image: Dan Burton / www.underwaterimages.co.uk)

The first was between 1770 and 1830 at Sunfish Bank (sunfish is the name given to the basking shark on account of its habit of basking in the sun with its back above the surface), about 30-40 km (19-25 miles) off the coast of Galway and Mayo near the edge of the continental shelf. The season was short, lasting only during April and May, but at least 1000 sharks were taken each year at the peak of the fishery. In the early 1830s, the sharks became scarce. Despite continued high prices for basking shark oil, the fishery collapsed and failed to recover.

A hundred years later, the west coast population of sharks was sufficient to support another fishery, this time working from the land at Achill Island. At the end of April each year, hardy Irish fishermen would go after the muldoans, as they were known, stretching an entangling net across Achill's Bay of Keem and taking up to 30 sharks a day until the end of the season in August. Up to 1800 sharks were taken each year between 1951 and 1955, but from 1956 the catch declined significantly. From 1956 to 1960 the average annual catch was 489 sharks, from 1961 to 1965 it dropped to 107, and then 50-60 per year until the fishery ended in 1975. A new fishery off Waterford in south-east Ireland in the same year, when 350 sharks were taken per year, confirmed that basking shark products were still in demand. At Achill Island, the sharks just were not there. It has been estimated since that the shark population declined by over 80 per cent in less than ten years. Even today, forty years after the fishing stopped, few sharks have returned. What is the impact of a population crash on undersea communities?

The marine environment has evolved over millions of years to maintain a dynamic equilibrium, and each component is important in the grand plan. Remove one element and order breaks down, the system thrown out of balance. Sharks are often the top predators in an ecosystem, and we do not know what happens when such an important component is removed. What are the knock-on effects further down the food chain? Sharks cull the sick, old and injured and scavenge on the dead, so their disappearance could have untold effects on not only local marine communities but also other commercial fisheries.

Conserving sharks

Of all the maritime nations with fishing fleets, very few monitor shark populations, and worldwide there are few reliable statistics. Only a handful of countries, such as the USA, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, have fishery management plans.

In the USA, the National Marine Fisheries Service's Atlantic shark fishery management plan sets quotas, oversees tagging programmes, as well as banning finning. It has limited the catching of many shark species in US controlled waters in the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. In spring 1997, it cut quotas of sharks by half, introduced quotas on small coastal sharks for the first time, and banned the commercial fishing of five shark species--the basking shark, whale shark, great white shark, sand tiger shark, and big-eye sand tiger shark. The conservationists are now considering restricting fishing permits, setting minimum sizes, and closing certain recognised pupping and nursery sites to fishing.

Such has been the concern worldwide for the fate of one species--the great white shark--that it has been singled out for individual attention, accompanied by an extraordinary U-turn in public attitude. At one time the great white was generally maligned, but this hostility has been replaced with concern by a more informed and an increasingly vociferous breed of shark-protectors.

Great whites, particularly the large breeding females, have been the target of a lucrative sports angling market, but in the 1990s an obvious decline in populations and the new, enlightened attitude culminated in the introduction of legislation in several countries. South Africa was one of the first to protect its great white sharks. Here, it is illegal to hook a great white within 200 nautical miles of the coast, and it has been so since April 1991. Tasmania, Namibia and the Maldives followed South Africa's example, and then on 24 September 1999 Malta became the first European country to ban the fishing of great whites.

Two years previously, there was a flurry of political activity elsewhere in the world. In April 1997, the US National Marine Fisheries Service finalised a rule that included a complete ban on commercial fishing of great whites and confined recreational fishing to a tag-and-release program along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts of the USA. Killing great white sharks in Californian coastal waters was made illegal on 2 August, when Governor Pete Wilson signed a bill which afforded the species permanent protection indefinitely.

Across the other side of the world, from 17 December 1997 the great white shark was officially protected in Australian Commonwealth waters. It was made illegal for people to take or kill these sharks, already considered 'vulnerable' under the Endangered Species Act, except for researchers with a scientific permit. Shark-fishing boats have now turned to shark-cage diving, and adventurous tourists who want to come face to face with one of the ocean's most spectacular predators have replaced sports anglers.

Other sharks are beginning to receive similar treatment. The sand tiger (grey nurse) shark in the USA and Australia, the whale shark in the Maldives, Philippines, the state of Western Australia and along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the USA, the shortfin mako in Canada, and the basking shark in USA, the Mediterranean Sea and in British waters are all now legally protected. Maybe sharks have a future after all.

Toolbox

The Museum's smallest members of staff are our flesh-eating beetles, Dermestes maculates, who strip carcasses to the bone.