Preparing for the voyage

A series of cruises took place around the coasts of Scotland and Faroe between 1868 and 1870. They showed that the deep sea varied in temperature and revealed some deep sea animals. But these cruises were short and gave limited information. A global expedition was needed to uncover more.

An expensive project

Portrait of Sir Charles Wyville Thomson

Two biologists, Professor William Benjamin Carpenter and Charles Wyville Thomson, proposed the Challenger expedition. They were convinced that life in the deep sea was possible despite the cold, darkness and high pressure. To be sure, they wanted to study the physics, chemistry, geology and biology of the deep sea.

With little opposition, the UK Treasury supported the idea, costing £200,000 – much more than £10 million in today’s money.

Nowhere near this amount had ever been spent on a scientific project before. It was the world’s first major expedition to study the deep sea.

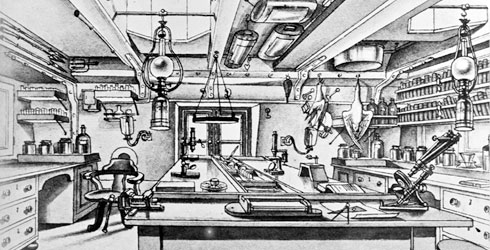

Preparing the ship

The HMS Challenger was immediately chosen for the voyage. All but 2 of the 18 canons on board were removed and the ship was fitted with a chemical laboratory, workroom, a library and even a dark room for the expedition's photographer. Tonnes of the latest equipment were loaded onto the ship, including over 400km (249 miles) of rope.

International collaboration

Five full time scientists and one artist were chosen to sail on HMS Challenger. The scientists came from a range of disciplines and nationalities, including Britain, Canada, Germany and Switzerland. Ever since, international collaboration has been an important part of oceanography.

Public interest

The Challenger expedition generated a lot of public interest and pride. It supported the idea of Britannia ruling the waves.

Popular newspapers printed articles about the expedition, not just when it began but throughout the voyage. The scientific journal, Nature, published information too. Scientists from the expedition wrote papers about their findings that were printed even before HMS Challenger had returned to Britain. There was a lot of excitement about their findings.

Toolbox

There are 27 km of specimen shelves in the Darwin Centre - the same distance as between the Museum and Junction 6 of the M1.