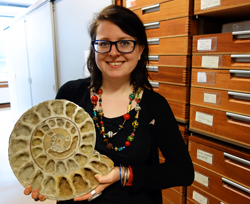

Zoë Hughes

The diverse lifestyles and clever adaptations of invertebrates made our fossil cephalopod and brachiopod curator fall in love with these characteristic creatures.

Early aspirations

Zoë discovered an appreciation for cephalopods while researching ammonites during her master's degree in taxonomy and biodiversity.

‘The thing about molluscs and shelled animals, and most invertebrates, is that they have lots of different solutions to deal with the problems of life,’ she says. ‘There’s a big range of how they eat, how they move around, how they look and protect themselves, and that’s really interesting.’

She now looks after fossil cephalopods (such as nautiluses and octopi) and brachiopods (marine shelled animals also called ‘lamp-shells’).

Super specimens

It’s rare for the soft bodies of ancient animals to be fossilised, but Zoë’s favourite specimen in her collection is an octopus from approximately 90 million years ago, where the animal’s soft remains are persevered in incredible detail.

The specimen is from Lebanon, where many well-preserved octopi and squid are found. ‘With some of the squids you can even see the ink sacs preserved,’ she says.

Zoë collects new specimens from the field, such as from recent expeditions to Morocco, and at huge mineral and fossil shows around the world.

Bringing the past to life

As well as entering numerous new specimens into the collection, Zoë has to do detective work. Some specimens have no labels or information and she has to figure out where they’ve come from and what they are.

‘Sometimes people come in wanting to see a specimen their great granddad collected and you’ve got to go and find it. Sometimes you open a drawer and there are just things in it you have no idea about. But it can turn into the best bit of the job if you succeed in sorting it out.’

Zoë also brings her collection to life through the Twitter accounts she has for each brachiopods and cephalopods, a blog for her collections, and by talking to the public, especially at events such as the annual Lyme Regis fossil festival, home to thousands of ammonites.