Behaviour

Collecting honey

Raiding honeybee colonies and sucking honey directly from the comb may seem suicidal for such a large moth. But adult death’s-head hawkmoths have numerous adaptations to help them survive:

- their legs are short and stout, with well-developed claws to help them climb around the combs

- other structures on the feet (the pulvilli and arolium) are highly reduced and non-functional, to prevent them clogging with honey

- the cuticle of the body is thick and covered in a dense pile of short scales to protect against the stinging attacks of worker honeybees

- the moths may have some resistance to honeybee venom

- the proboscis of a death’s-head hawkmoth is short, stout and pointed so it can pierce capped honey cells and suck up the viscous honey inside more easily

Squeaking

Adult death’s-head hawkmoths are famous for making loud, high-pitched noises.

The moths squeak loudly when disturbed, but also when inside honeybee colonies.

Some scientists consider these squeaks similar to the piping sounds produced by queen honeybees, which make the worker bees stop moving around (the freezing response).

However, others dispute this as no-one has seen worker bees freeze in the presence of moths (Moritz et al 1991).

Acherontia atropos epipharynx - this small flap at the base of the proboscis enables the moth to 'squeak'.

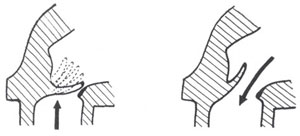

The squeak is produced by a small internal flap at the base of the proboscis called the epipharynx. The noise is made up of 2 parts:

- Air is drawn in and the mouth rapidly opened and closed by rhythmic movements of the epipharynx. This produces a rapid train of 40–50 distinct pulses each lasting about 160 milliseconds.

- The air is then expelled with the epipharynx held up, producing the second part of the sound - a single, sustained note lasting about 60 milliseconds.

This process is repeated 40 to 50 times to produce the whole squeak.

Honeybee disguise?

Guard bees often attack death’s-head moths as they try and enter the hive (Moritz et al, 1991) but once inside, the defending workers rarely attack.

Some scientists suggest the skull mark on the moth looks rather like the face of a worker bee (Rothschild, 1985). But the moths raid at night, and it’s dark inside the hive anyway.

Acherontia atropos markings may resemble a worker bee's face

Others (Moritz et al, 1991) have compared the odours emitted by honeybees and death’s-head hawkmoths. They extracted the surface hydrocarbons from both honeybees and Acherontia atropos adults and compared them using gas chromatography.

The honeybee extracts consisted of 4 compounds:

- 2 major components - the saturated fatty acids hexadecanoic acid (palmitic acid) and octadecanoic acid (stearic acid)

- 2 minor components - the unsaturated fatty acids (Z)-9-hexadecenoic acid (palmitoleic acid) and (Z)-9-octadecenoic acid (oleic acid)

The moth extracts were more complex, with many more compounds in the mix, but all 4 honeybee fatty acids were present. So, the death’s-head hawkmoths seem to be chemically 'invisible' to bees.

Honeybees are acutely sensitive to odours and can even distinguish between nest mates and non-nest mates. So, why are they fooled by such apparently gross chemical camouflage?

The answer may lie in their squeaking. But the moths use the same structures for squeaking and eating.

Scientists have found that after drinking honey, the moths can only make clicking sounds and are unable to squeak again for 5 hours (Newman, 1965).

So, if the squeak does pacify the bees, the moths must escape the hive quickly before the bees realise something is wrong and attack.