Behaviour

If a colony becomes overturned by a fish or current then it is able to right itself and avoid being smothered by sediment. This behaviour only occurs at night when the coral polyps extend for active feeding.

To overturn, the colony fills its stomach with sea water so it becomes bloated, and then alternatively jets water from one side and then another of the colony.

This causes the colony to rock back and forth until the centre of gravity is surpassed and the colony rapidly flips upright.

The entire process takes a few hours until the final flip occurs in an instant.

Large colonies are less able to re-orient themselves because the weight of the skeleton increases with the volume of the colony, and the power of the water jets is related to the surface area.

Once overturned, large colonies are more likely to die by smothering in the sediments.

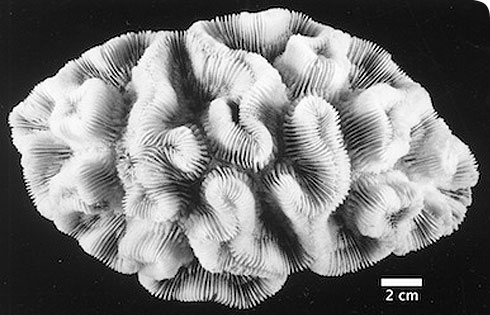

This places an upper limit on the size of the colonies and explains why in most habitats colonies rarely grow to more than 10cm.

Toolbox

Glossary

Corallite

The skeleton of a coral polyp.

Columella

Small column-like structure.

Meandroid

Colony composed of corallites in linear series within the same wall.

Mesenteries

Fleshy septa connected to an oral disk. Mesenteries occur in pairs and flow like curtains.

Septa

Partitions between two cavities.