Behaviour

Desmodesmus can change its form in response to changing environmental conditions, exhibiting phenotypic plasticity.

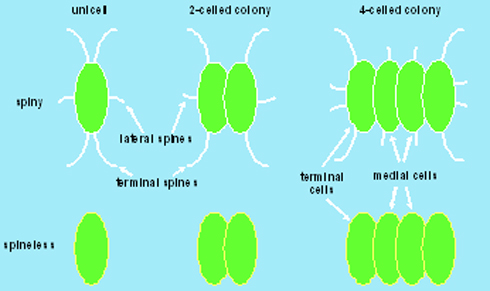

The most prominent morph is the colony, however, it can also produce a unicellular morph.

Unicells

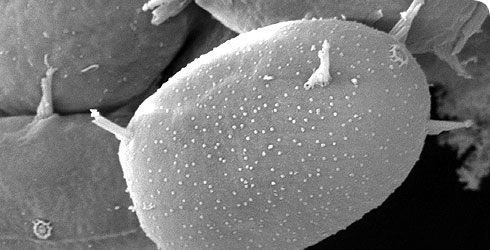

The unicell is produced within the parent wall of a cell of the colony and when it is released it has the same wall morphology and spines as a cell of the colony, except that the unicell has more spines.

This morphological change can be ‘triggered’ by an increase in the concentration of nitrogen or phosphorus.

This phenomenon has been observed in the field and the laboratory.

Different genera names (Franceia, Chodatella and Lagerheimia) have been given to the unicells (depending on the spine pattern).

This happened because the unicells were observed from natural collections and the investigators did not realise that the unicells were an alternate stage of the colony.

Subsequently, when Desmodesmus was isolated and grown into culture that was free of other organisms (axenic), unicells formed in the clonal culture.

Eventually, the ‘triggers’ were identified and now the unicell to colony transformation can be controlled by manipulating the nutrient concentration. This transformation can occur in a 24-hour period.

Types of unicells and colonies formed by Desmodesmus subspicatus.