Biology

These aphids are usually creamy white in colour, sometimes a very pale green, with a very pale cuticle except for black antennae.

Aphids have an unusual biology that involves being completely asexual for most, if not all, their life cycle.

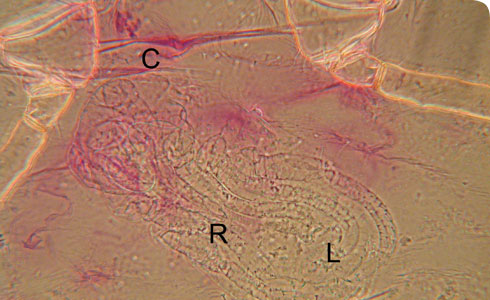

This form of reproduction is called parthenogenesis and involves the unfertilised adult female reproducing clones of herself with great rapidity.

She gives birth to live first-instar nymphs - vivipary - as soon as she has reached maturity. By this time embryos are already forming inside her as-yet-unborn progeny. This situation enables aphids to ‘telescope’ generations, allowing enormous populations to develop very quickly when food plants are in optimum condition.

The absence of an egg stage speeds things up even more. This can lead to gardeners expressing sentiments like, “Where on Earth did they come from - they weren’t here last week!”

The majority of the world’s aphids inhabit cooler climes where they would not survive winter conditions as vulnerable soft-bodied insects. This is where aphid biology exhibits something of a ‘trump card’.

After several generations of parthenogenetic females, many aphid species respond to the shortening autumnal day-length by producing nymphs that develop into sexual morphs - males that are usually winged and egg-laying females (known as oviparae) that are almost always wingless.

In this one generation, mating and exchange of genetic material occurs and the fertilised oviparae lay eggs in sheltered situations on twigs or in bark fissures, where they will normally survive the winter.

The individuals that hatch from these eggs in spring are, once again, parthenogenetic but look somewhat different and are called fundatrices (literally ‘stem mothers’).

As if this overwintering phenomenon, which is known as a holocycle, were not enough many aphids (including Rhopalomyzus lonicerae) mate and then lay eggs on 1 host plant species (termed the primary, usually woody, host), but spend the summer months on a completely unrelated secondary (usually herbaceous) host.

The actual change of host occurs as a result of the production of winged individuals on the primary host, which then leave that host. A small proportion of these ‘spring migrants’ will be lucky enough to locate the correct secondary host on which their enormous fecundity will allow rapid population growth. In autumn it will be winged individuals that seek out their overwintering host once again.

Aphids completing their life cycle on only one host are said to be monoecious or autoecious, and those with host-alternation to be dioecious or heteroecious.

Rhopalomyzus lonicerae, with grass summer hosts and Lonicera winter hosts is said to have a dioecious holocyclic life cycle.

Where there is no pronounced cold winter many aphids remain parthenogenetic on what are nominally their secondary hosts throughout the year, and the colonies are then termed anholocyclic.

Many aphid crop pests in warmer parts of the world are anholocyclic, especially on cereals, monocots and herbacious dicotyledonous plants. Even in temperate zones some aphid species are entirely anholocyclic.