Rhopalomyzus lonicerae

Aphids are true bugs - members of the order Hemiptera whose species all feed on liquid food via modified tubular mouthparts known as stylets. These are guided by a structure called a rostrum.

Adult aphids are very diverse in appearance but most have walking mobility, some can run surprisingly quickly and some are even able to jump when threatened - they are what we call saltatorial.

All aphids are phytophagous - they feed on plants by ingesting their sap.

Some species are highly polyphagous, feeding on many different plants, and may be notorious agricultural pests.

The common names blackfly and greenfly are often applied to colonies of aphids on cultivated plants, but aphids actually come in many colours including:

- whitish (like Rhopalomyzus lonicerae)

- brilliant yellow

- purple

- many shades of red and pink

- a bluish tinge occurs in some species thanks to waxy secretions

Occasionally a single colony can contain individuals of several different colours - most commonly a mixture of rose-pink and green.

Most aphids have both winged and wingless forms (morphs) and some have as many as seven distinct morphs.

Rhopalomyzus lonicerae is an excellent example of an aphid with a common yet highly specialised life cycle, abundant in Britain yet relatively unknown.

Species detail

-

Distribution

The Museum has specimens of Rhopalomyzus ionicerae from many countries in the northern hemisphere. Find out more about this species’ range and what it likes to eat.

-

Biology

Aphids have an elaborate lifecycle that means they can expand dramatically to huge population sizes. Discover how this clever insect reproduces and can ‘telescope’ generations when food is plentiful.

-

Conservation

Many aphids are notorious pests. Rhopalomyzus lonicerae does sometimes feed on cereal crops but is only regarded as a minor pest, and it caused only a minor nuisance when it appeared in large numbers in the Museum’s wildlife garden in summer of 2010. Find out how aphids can be controlled naturally.

-

References

Get reference material for Rhopalomyzus lonicerae.

Images

An adult apterous female and nymphs feed on their grass host. When the aphids are undisturbed and feeding, their antennae are swept over their backs.

© Harry Taylor

An adult apterous female and nymphs feed on their grass host. When the aphids are undisturbed and feeding, their antennae are swept over their backs.

© Harry Taylor

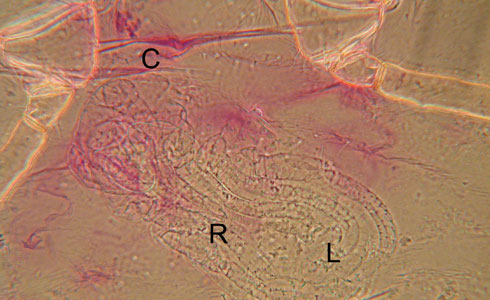

On a cleared and slide-mounted aphid, a single embryo is visible through the mother’s body wall, close to being born. Its head is to top-left, one compound eye is beneath the letter C. The feeding rostrum ends immediately above the letter R and the legs curve around the letter L.

© Jon Martin

On a cleared and slightly stained Rhopalomyzus lonicerae specimen, the head with compound eyes and antennal tubercles can be seen, with the rostrum clearly visible even though being ventral and seen through the cleared body.

© Jon Martin

On a cleared and slide-mounted adult the apical segment of the rostrum can be seen with the stylet channel running down its central axis.

© Jon MartinAbout the author

Dr Jon Martin

Former Curator of Hemiptera, Department of Entomology.

A word from the author

"This particular species aroused interest in the Museum’s own wildlife garden, where an enormous population had completely covered the lower surfaces of blades of the semi-aquatic grass Phalaris arundinacia in July 2010.

"It is not a notorious pest, nor is it spectacular in its appearance. It is a typical aphid whose story enables us to share with the viewer a very highly-specialised life-cycle that involves virgin birth, alternation of host plants and winter survival in the form of tiny eggs."