Behaviour and disease

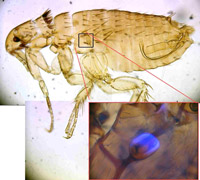

Bubonic plague has killed millions of people worldwide. Xenopsylla cheopis fleas transmit the disease.

The resilin pad is shown in blue. This is squeezed as the leg muscles operate and all of the energy imparted via the leg muscles is released from the resilin pad in about a millisecond. © Darren Wong, Dr David Merrit

Behaviour

When jumping, fleas use a pad of elastic-like protein called resilin above the hind legs - this stores huge amounts of energy.

In a millisecond, the flea can release as much as 97% of this stored energy for a massive leap, or series of leaps.

Fleas are capable of jumping non-stop for many hours - or even days - without a rest.

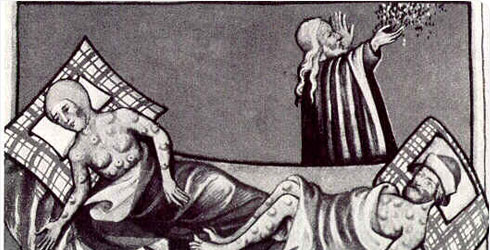

Disease

Although several species of flea transmit bubonic plague between rodents and humans, Xenopsylla cheopis is recognised as the most common vector, or carrier, of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis.

Bubonic plague remains endemic in some parts of the world where the plague bacterium lives in small mammal populations such as marmots and does little harm.

Occasionally, these rodents come into close contact with rats, and the fleas carrying the plague bacterium transfer from the marmots to the rats and infect them. As the fleas increase in number, more rats become infected, and so on until an epidemic breaks out in the rat population.

Fleas like to feed on blood at body temperature. When infected rats die, the infected fleas leave to look for a new host. This might be another rat, or a human.

As the flea feeds on its human host, a few bacteria pass into the bloodstream.

The bacterium blocks the flea’s digestive system and causes the flea to continue biting and trying to feed.

Eventually the flea dies of starvation but not before it has successfully transmitted the plague bacterium to multiple people.

Over the centuries many theories were put forward as to how plague was transmitted, but it was not until the 1890s that Alexandre Yersin identified the plague bacterium we know as Yersinia pestis in rats and humans that had died of the plague.

Yersin originally named the bacterium Pasturella pestis but it was renamed in his honour in the 1960s.

Researchers had suspected for a long time that fleas transmitted the plague between rats and humans, but it wasn’t until 1910 that it was confirmed.