Dwarf elephant tooth

This fossil tooth and jawbone was one of the first pieces of evidence that miniature elephants once lived on Cyprus. It was discovered by intrepid collector Dorothea Bate, the first female scientist employed at the Natural History Museum.

Dorothea Bate (front right) in a photograph of the Museum's Geology Department in 1938.

Pioneering woman

Dorothea Bate was a self-taught, zealous natural historian. In 1897 she enthusiastically talked her way into a job at the Museum aged just 19. She was paid only for the number of specimens she collected and prepared.

This continued for nearly 50 years until, aged 70, she finally received her first official appointment: Officer in Charge of Tring, our Museum in Hertfordshire.

Bate’s collecting expeditions began in Wales, where she found a cave containing fossil mammals. Encouraged by palaeontologists at the Museum she published a report on these finds aged only 22, then set off to explore further afield.

Dwarf elephant discoveries

On Cyprus, Bate hunted for caves in which to look for bones. She ventured to desolate places, facing challenging living conditions, illness and the danger of violent crime.

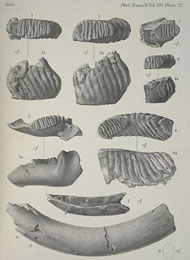

Illustration of dwarf elephant fossil remains found by Dorothea Bate.

Her bravery and perseverance were rewarded when in 1901 she found fossils of what looked like elephant teeth, only much smaller. They were the first evidence on Cyprus of the phenomenon of island dwarfism in elephants.

The dwarf elephants evolved from the now-extinct straight-tusked elephant, Palaeoloxodon antiquus. These large elephants probably swam to Cyprus from mainland Europe. They adapted to the island environment, which may have had limited food, by getting smaller. The lack of predators also meant there was no need to stay big. Eventually, adult elephants became approximately the same size as pigs.

Crucial questions

Bate not only accurately identified her finds as small elephants, but asked ‘why are they small?’

Her interest in the evolutionary relationship between animals and their environments grew. She expanded her inquiries, beginning the science of archaeozoology – the study of past relationships between animals and humans.

Following in Bate's footsteps

Today, Museum scientists Adrian Lister and Victoria Herridge are studying the effects of dramatic environmental changes over the last 800,000 years on the evolution and survival of dwarf elephants.

They are using modern techniques to date fossils more accurately. This work could eventually help us understand how mammals might respond now to climate change.

Further information

- Visit the dwarf fossil tooth in our new Treasures Cadogan Gallery.

- Uncover more about the life and achievements of Dorothea Bate.

- Watch a video about the world’s smallest mini mammoth, revealed by recent examination of Bate’s fossils and field diaries by Museum scientists.

- Find out more about current Museum research on the dwarfing of fossil mammals on Mediterranean islands.

Vote for your favourite treasure

Is this your favourite Museum treasure? Let us know by voting in our poll.