Great auk

The great auk, Pinguinus impennis, is one of the most powerful symbols of the damage humans can cause. The species was driven extinct as a result of centuries of intense human exploitation.

Colony of guillemots, Uria aalge, relatives of the extinct great auk. © David Tipling Photo Library

Unsustainable slaughter

Large dense colonies of this flightless bird once gathered in summer on remote islands off eastern Canada, Greenland, Iceland and Scotland. Easy prey for hunters, they were slaughtered in huge numbers until the late 1700s for meat, eggs, feathers and oil.

European fisherman and whalers devastated the largest colony in Newfoundland. A 1775 petition to stop the massacre failed.

Enigmatic charm

Great auks have always appealed to humans. A 4,000-year-old burial site in Newfoundland contained 200 great auk beaks, thought to have been attached to ceremonial clothes.

Great auk feeding frenzy, painting by Bruce Pearson. © www.brucepearson.net

In the early 1800s, the rarer the birds became, the more desirable they seemed. Demand from museums and collectors dealt the final blow.

Agile and streamlined in water, great auks moved clumsily on land, only coming ashore to breed. They could only waddle awkwardly at human walking pace. In 1844 a final unfortunate pair fled in vain from hunters, their single egg smashed.

By the mid-1850s the species was extinct.

A home in Tring

The specimen on display in our Treasures Cadogan Gallery is believed to have been captured in Iceland in 1837. Many years later, Walter Rothschild acquired it for his Zoological Museum in Tring, Hertfordshire, which opened in 1892.

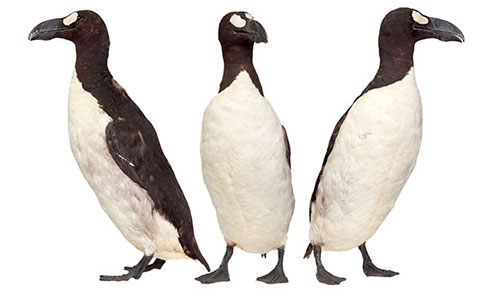

Specimens on display at the Museum at Tring.

Rothschild began collecting in 1875, aged 7, and went on to amass more natural history specimens than anyone before. He selected only the finest pieces, prepared by experts.

The scientific works he published advanced our knowledge about many new and extinct species, including the great auk.

Despite his family's wealth, Rothschild struggled financially and had to sell most of his bird collections. This great auk was one of the treasured specimens he kept back for himself, a poignant memento of a recklessly exterminated species.

Rothschild left his collection of 2.5 million specimens and 30,000 books to the Natural History Museum when he died in 1937. It is the largest single gift the Museum has ever received.

Further information

- Visit the great auk specimen in our new Treasures Cadogan Gallery.

- Discover the fascinating history of the Natural History Museum at Tring, from its origins in Rothschild's shed, and learn about the remarkable man himself.

- Uncover other tragic examples of extinctions caused by humans.

Vote for your favourite treasure

Is this your favourite Museum treasure? Let us know by voting in our poll.