Moa bone fragment

Moa were enormous extinct birds from New Zealand. This fragment of bone provided the first evidence that they existed. Richard Owen, the Natural History Museum's first superintendent, used his great anatomical knowledge to predict that it belonged to a giant bird that couldn't fly.

Richard Owen standing next to a complete moa skeleton (we now know they wouldn't have had such an upright stance). He is holding the bone fragment he used to predict the existence of these giant birds.

Masterful anatomist

Richard Owen’s aptitude for understanding animals by examining their anatomy was unrivalled. He pioneered the science of comparative anatomy, studying the physical similarities and differences between species. His skill and fierce ambition took him to the top of his profession.

At the time, Europeans were still exploring the world, returning home with creatures beyond their imaginations. For example, when the duck-billed platypus from Australia was discovered, many people thought it was a fake.

Owen was the expert of choice to examine the curious new finds. This privileged position meant he was the first to describe hundreds of new species.

Bold prediction

Owen’s most dramatic scientific triumph came in 1839 when he studied a short fragment of bone discovered a few years earlier in New Zealand. He meticulously compared it with bones from 14 other species, including humans, kangaroos and even a giant tortoise.

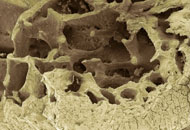

Scanning electron microscope image showing the honeycomb structure of a bird bone. © Steve Gschmeissner / Science Photo Library

The honeycomb structure inside was like that of bird bones, making them light enough for flight. But this bone was much bigger than any known bird’s, even ostriches.

Owen deduced it must have belonged to an even larger extinct flightless bird. Four years later the world was astonished when more bones revealed he was right.

No match for humans

Moa were unique to New Zealand. The 2 largest species, Dinornis robustus and Dinornis novaezealandiae, could reach up to 2m tall (back height), making them among the tallest birds in the world.

No one in Europe had seen anything like this monstrous bird before. By the time Europeans first arrived in New Zealand in the 1760s, they had already been hunted to extinction by the first human settlers. It took Owen’s genius to resurrect them.

Further information

- Visit the moa bone fragment in our new Treasures Cadogan Gallery.

- Uncover more about the demise of the moa and other recent extinctions.

- Find out about the life and achievements of Richard Owen.

Vote for your favourite treasure

Is this your favourite Museum treasure? Let us know by voting in our poll.