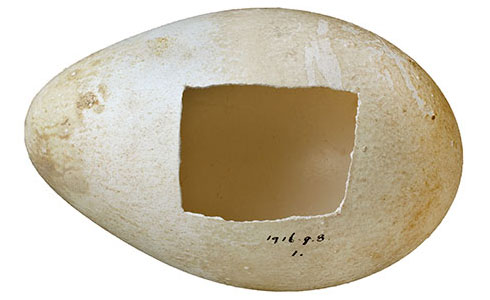

Emperor penguin egg

This is 1 of only 3 penguin eggs collected when fresh under extremely harsh conditions in Antarctica by members of Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition team. It was hoped that the embryos inside would confirm a link between reptiles and birds.

Emperor penguins, Aptenodytes forsteri, only live in Antarctica. © Art Wolfe / Science Photo Library

Dual mission

The main goal of Scott’s ill-fated Antarctic expedition of 1910-1913 was to be the first to reach the South Pole. But there was another less well-known mission – to collect as much scientific data as possible from the frozen continent.

Edward Wilson, the expedition’s chief scientist, particularly wanted to test the hypothesis that studying emperor penguin embryos would show an evolutionary link between birds and reptiles.

Bitter endurance

Emperor penguins live only in Antarctica, and they lay eggs in the middle of winter.

In 1911, Wilson, his assistant Apsley Cherry-Garrard and Henry Bowers left the hut at Cape Evans to walk a punishing 100km to the only breeding colony known at the time. For 5 painful weeks they pulled heavy sledges in complete darkness at -40˚C. Never before had anyone travelled in such bitter cold.

Bowers, Wilson and Cherry-Garrard before leaving on their egg hunt.

Cherry-Garrard later told the harrowing tale of how their bodies shook so violently from the cold they thought their bones would break, calling it the worst journey in the world.

With great difficulty the men collected 5 eggs, putting them inside their mittens for safety. Still, 2 broke on the trek back.

Delayed by war and death

The 3 surviving eggs were carefully cut open and the embryos removed and pickled. Back in Britain they were sliced and mounted onto 800 microscope slides. But study of the specimens was delayed by the First World War and the death of Richard Ashton, the specialist embryologist assigned to analyse them.

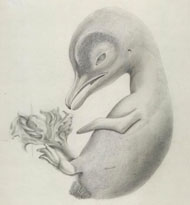

Pencil drawing of a penguin embryo before sectioning, by Dorothy Thursby-Pelham (colleague of embryologist Richard Ashton).

By the time of their eventual study, published in 1934, science had moved on and the theory of a link between an organism’s embryo development and its evolutionary history had been rejected.

The embryos did not provide evidence for the link between birds and reptiles after all.

Tragic end

Wilson and Bowers were selected to travel with Scott for the final push to the South Pole in early 1912. They perished with him on the return journey, having been beaten to the pole by their Norwegian competitors and trapped by a storm.

Scientific legacy

The expedition’s scientific work helped lay the foundations for Antarctic science. Researchers from around the world still use data gathered on the expedition as a baseline.

The emperor penguin eggs Scott’s men collected may not have proved a scientific breakthrough, but they are a fragile symbol of the quest for knowledge.

Further information

- Visit one of the emperor penguin eggs in our new Treasures Cadogan Gallery.

- Watch a video about the worst journey in the world and discover more about the terrible hardships Wilson, Cherry-Garrard and Bowers suffered.

- Discover how Edward Wilson’s artistic talents supported the expedition’s scientific aims.

- Find out about Antarctic research today, from extreme bacteria to climate change.

Vote for your favourite treasure

Is this your favourite Museum treasure? Let us know by voting in our poll.