Neanderthal skull

The Natural History Museum looks after the first adult Neanderthal skull ever discovered. The specimen helped start the science of palaeoanthropology - the study of ancient humans.

Neander Valley Neanderthal specimen, identified in 1856.

Neanderthals and our family tree

The skull was found in 1848 in a quarry in Gibraltar. At first, its significance wasn’t recognised. But 8 years later amateur naturalist Johann Fuhlrott identified a similar skull in the Neander Valley in Germany, which was named as a new species of human, Homo neanderthalensis, in 1864.

This sensation meant the first skull was revisited, and it too was found to be a Neanderthal fossil.

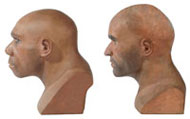

Unlike modern humans, Neanderthals had a heavy brow ridge, low forehead and a protruding central face. But their brain was about as big as ours and larger than earlier human species.

Reconstructions of a Neanderthal (left) and modern human.

Our species, Homo sapiens, is the only surviving human, but we know of about 20 other human-like species that are now extinct. We used to think Neanderthals were our ancestors but now we believe they are among our closest human relatives, more like cousins.

Out of Africa

In the 1980s, Museum scientist Chris Stringer and other researchers started to develop the Out of Africa or Recent African Origin model of human evolution. The theory that all modern humans descended from recent African ancestors became widely accepted.

Neanderthals evolved from species that left Africa earlier than modern humans and then continued to evolve separately in Europe and Asia.

Vanguard cave, Gibraltar, where Neanderthal artefacts have been found.

Final resting place

Shortly after modern humans moved into Europe around 45,000 years ago, Neanderthals became extinct. New competition probably made life even more difficult for them during a time when rapid climate change was already making food scarce.

Fossil finds and other archaeological evidence indicates Gibraltar may have been one of the Neanderthals’ last refuges. Museum scientists are working with dating laboratories to accurately estimate the age of this skull.

Part of you?

Palaeoanthropology remains a dynamic science, with this Museum at its forefront. Studying specimens such as this skull is helping us to build a more complete picture of human evolution.

Recent DNA research has revealed surprising results, such as the discovery of Neanderthal DNA in some modern humans. This suggests a small amount of interbreeding between our populations. So perhaps Neanderthals aren't completely extinct after all.

Further information

- Visit the Neanderthal skull in our new Treasures Cadogan Gallery. It will be alternated with the Broken Hill skull.

- Discover what fossils, DNA and other evidence reveal about what Neanderthals were like and how closely we’re related.

- Compare Neanderthal and modern human skulls with our 3D skulls interactive.

- Meet our early human family.

Vote for your favourite treasure

Is this your favourite Museum treasure? Let us know by voting in our poll.

Listen to the Treasures podcast

Neanderthal skull story

Museum human origins expert Chris Stringer, model-maker Jez Gibson-Harris and acoustics researcher Anna Barney build a picture of our ancient human relative, starting with the first skull.

Listen to or download the Neanderthal skull story 8min 18sec, 11.4MB